Or: why “where” your MCP server runs matters just as much as “what” it does.

TL;DR Running an MCP Server on localhost is a night-and-day difference compared to running one remotely.

Local == single user, implicit trust, almost zero auth to the server.

Remote == multi-user, explicit trust, real authentication to the server, security trimming, token exchange, and all the headaches (and rewards) that come with it.

1. Introduction – Context in Two Senses

When people hear Model Context Protocol (MCP), they usually think about the data context an LLM needs—documents, code, tickets, whatever.

Less obvious, but just as important, is the deployment context in which the MCP server itself lives.

- Local sandbox: One dev, one laptop, one loopback interface.

- Remote service: Many users, many clients, many downstream systems, and a permanent address on the public internet (or barring that, at least on your private network).

Those two worlds demand radically different security and architecture choices.

MCP has only existed as a “thing” since late 2024, and has only really gotten popular (and only gotten serious with auth specs) as of the last couple of months, and the mere ~6 or so months of its existence is part of the reason why the state of affairs with respect to running these in advanced remote scenarios is relatively immature. (Yes, I said it—for those on the agentic hype trains, don’t @ me.)

2. Local MCP – The Joy of Single-User Simplicity

I am going to pick on the GitHub MCP Server as an example, because despite it being relatively popular—with GitHub being one of the first things developers would likely want to connect to with agentic tools—it is imbued with all the naïveté I’ve come to expect in the MCP servers that I’ve looked at thus far, making it effectively a non-starter for sophisticated enterprises who would wish to run it remotely (unless you applied some serious elbow grease—more on that later).

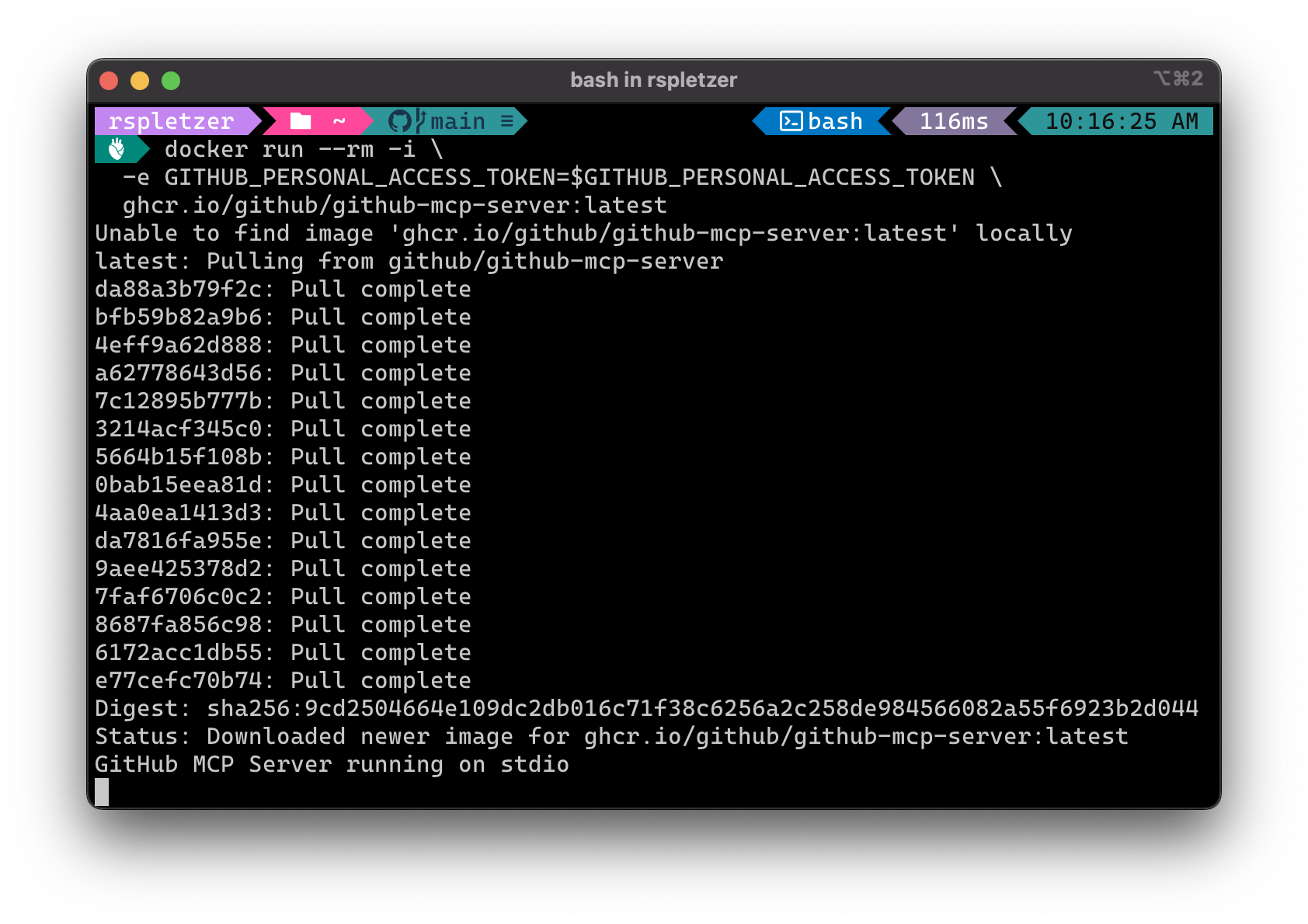

Running the GitHub MCP Server locally could like the following:

# Provide your GitHub (preferably Fine-Grained) Personal Access Token

read -rsp "GitHub PAT: " GITHUB_PERSONAL_ACCESS_TOKEN

# Run the GitHub MCP Server

docker run --rm -i \

-e GITHUB_PERSONAL_ACCESS_TOKEN=$GITHUB_PERSONAL_ACCESS_TOKEN \

ghcr.io/github/github-mcp-server:latest

You’ll notice that last message: GitHub MCP Server running on stdio.

stdio stands for “Standard Input/Output” and represents an inter-process communication approach to providing an MCP

Server to a local MCP client, like Visual Studio Code.

stdio only is feasible for local scenarios, so that leads us to the next logical question: how would we make the

GitHub MCP server available over HTTP / SSE (Server-Sent Events) transport, or the even more recent and modern

Streamable HTTP transport (which literally was conjured up

alongside the MCP specs in the last few months)?

The answer to this question illustrates a key point: The GitHub MCP Server doesn’t support HTTP + SSE, and thus doesn’t actually support being run in a remote setting at all. (Yet.)

Many of the MCP servers that have been created over the last few months didn’t take into account remote scenarios, as they were coded and designed purely with these local clients in mind.

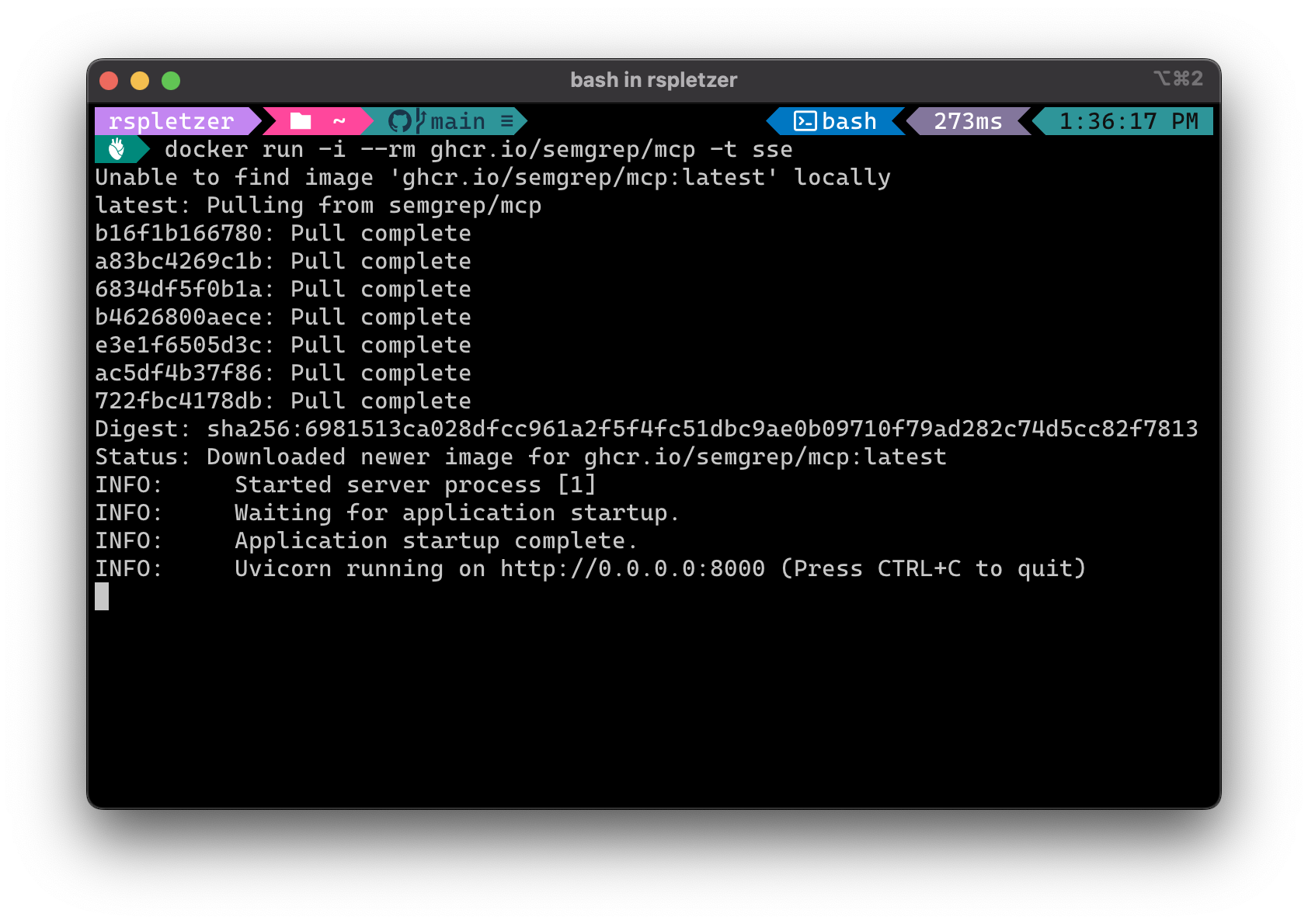

So let’s turn our attention to an MCP Server that does have HTTP+SSE transport, the Semgrep MCP Server:

# There are multiple ways to run this, but to stay consistent we'll run it with docker:

docker run -i --rm ghcr.io/semgrep/mcp -t sse

The examples above just show how to run the servers, but in reality, when consuming via something like Visual Studio

Code, you would wire this up in something like .vscode/mcp.json so your IDE is aware of how to start it up when you

open a project.

2.1. Why No Auth Feels Okay

You may see this as a developer and think “I don’t get it, this seems totally fine so far”—and you may actually be correct. See, running these MCP servers locally has certain aspects to it:

-

Physical access is implicit authentication.

If you can hit

localhost, you’re already inside the blast radius (your laptop). -

One tenant = one permission set.

There’s no question whose the user is in this scenario, it’s all just you.

The server can safely assume “allow everything.”

To be honest, this is what developers like: developer ergonomics reign supreme when there is zero OAuth dance, no JWT debugging, no credential managers to deal with. It’s the fastest path from idea to working prototype. But it is these same ease of use tendencies for working on our local machine that can make us blind to the very real issues of trying to make these types of MCP servers work in a remote setting. For example, lack of HTTP transport aside, if you attempted to move the GitHub MCP Server into a remote setting, whose personal access token are you going to use? And if it’s a privileged personal access token, how do you know the user behind the calling client isn’t accessing repos or other data that they don’t have access to natively?

2.2. The Boundaries of “Safe Enough”

The moment you expose that port beyond loopback—say, you port-forward via ngrok so a coworker can demo your MCP server—all bets are off. Anyone who has the URL owns your MCP, and by that, any permissions you granted to that GitHub personal access token. That’s fine for a five-minute demo, catastrophic for anything longer.

If all MCP was is a way to wrap external resources (be they your local file system, or remote database or REST API, etc.) with your own local MCP servers to provide it to your own local agent tools, then there would be pretty much zero issues here, and no need for this blog post—it would just be developers doing their thing on their local dev machines. But the issue with MCP right now is it is trying to be more than that, and this is where pretty much any off-the-shelf MCP server is going to struggle in a remote setting.

In a very real way, many available MCP servers today are at about the same level as a “Hello World” local web app or

API running on localhost with no authentication (and without auth, further you really have no concept of multiple

users or multi-tenancy)—if you’ve created something like that, I would hope that you would understand intuitively that

it in no way could just simply go to production as-is.

3. Remote MCP – Welcome to Multi-User Reality

Move the same MCP server to https://mcp.acme.dev and everything changes.

3.1. Authorization is Now Mandatory

Every request must identify who is calling. The mainstream way is OAuth / OpenID Connect (OIDC), and the MCP specs themselves call this out as “optional”, but something that SHOULD be implemented for HTTP transport scenarios—in reality, authorization was an afterthought added to the spec after many individuals and companies pointed out the issues of not defining a way to handle authorization, since not only would it likely lead to naïve security hazards, but would hurt the interoperability and discoverability aspects of the ecosystem.

A call to an MCP server with authorization would look something like the following with a JWT access_token passed in

the Authorization HTTP header with the Bearer scheme:

POST /query

Authorization: Bearer eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1N...

...

This:

- Validates the JWT access_token’s signature against your identity provider’s (IdP’s)

jwks_uriwhich provides the public keys and is discoverable via the OpenID Connect metadata endpoint. - Rejects expired JWT access_tokens (concretely, ensuring the current date time is not past the

expclaim in the token, represented Unix epoch time). - Checks that the JWT access_tokens

audclaim is in fact the string you expect that represents your MCP resource, not an arbitrary API. (Theaudis often represented as a GUID, or some type of unique identifier for your target resource.) - In cases where there is a human user involved, it should utilize something like the user’s

sub(subject) claim from the JWT access_token, to understand who the user is for filtering for downstream calls. (Which, no server I’ve ever seen so far does this—the validation typically stops with only the checks above, if you’re lucky that they’ve done all of them right and not missed something. Beyond this authorization check, they typically don’t implement further fine-grained authorization logic for security trimming, because frankly that can get enterprise-specific and is difficult to assume or make configurable for a wide variety of scenarios.)

A reverse proxy (→ Envoy, Traefik) can handle this so your app code can assume a verified user context—but again, you may need that user context in your actual MCP server code to make further authorization determinations. Most off-the-shelf MCP servers do not—and often cannot—make those authorization decisions for you.

Note that we just say “Authorization” here and not “Authentication”—that is because technically the authentication portion happens between the client and the identity provider (IdP) you’re talking to, like Okta or Microsoft Entra ID or a consumer third party identity provider like Google or Apple or Microsoft.

3.2. Authorization & Security Trimming

Authentication (AuthN) only says “Alice is Alice.” Authorization (AuthZ) answers “Which docs/repos/items/objects can Alice actually read?”

An enterprise MCP ecosystem could often fan out to services like GitHub, Jira, Confluence, Artifactory, Microsoft Graph, or a vector DB keyed by user or security group ID’s. That means:

- Row-level filters:

SELECT … WHERE user_id = <aliceUserId> OR group_id = <securityGroupIdAliceIsIn> - Search ACLs: e.g. Elasticsearch or OpenSearch query-time filters

- Downstream: on-behalf-of (OBO) flows; exchange Alice’s inbound JWT access_token scoped for the MCP server resource with your IdP for another JWT access_token to access an API that accepts user-scoped tokens from your IdP for purposes of security trimming.

Fail to trim, and your nice AI agent becomes a data-leak vending machine.

3.3. Multi-Tenant Isolation

Thus far we have approached local and remote scenarios only from the standpoint of a developer who us using local tools to connect to local and remote MCP servers.

But MCP servers are not destined just for developer tools—they can and will be used in scenarios like enterprise chatbot assistants, where a lot of the same remote lessons apply with regards to user identity and security trimming, etc.

But what about when you’re running a multi-tenant SaaS product that has agentic capabilities that wish to consume MCP Servers?

You are now storing embeddings, indexes, caches, and data for many customers. Everything needs a partition key. Consider:

$TENANT_ID:$DOC_IDkeys in Redis.- Distinct Milvus/Mongo/Postgres collections/tables/databases per tenant.

- S3 prefix per tenant (

s3://mcp-prod/tenants/$id/). - Database filters based on tenant ID.

When it comes to running products, you are now firmly out of the realm of off-the-shelf MCP servers and now in a place where you are creating them from scratch—sure, you can derive some “inspo” from some of the MCP servers out there, but what you’re creating inherently now has to be catered to your products and SaaS ecosystem.

These considerations even extend to scenarios beyond your core products and into tools your customers may be using, like Microsoft 365 Copilot, where they may want to connect their own enterprise Copilot chat to MCP Servers that wrap various APIs of your products, and you have to provide facilities for users at your customer’s enterprise to authenticate to provide proper security trimming, in much the same way that you authenticate to anyone of a number of Slack apps as a user to connect to various tools.

4. Consumer Patterns Drive Security Posture

This table gives a brief breakdown of some of the remote authentication patterns for various scenarios.

| Pattern | Who calls MCP? | Typical Auth Flow |

|---|---|---|

| IDE plugin (Visual Studio Code, JetBrains) | The developer’s desktop | Often local MCP → no auth. If remote: OAuth device flow (perhaps with PKCE); store refresh token in keychain. |

| Web/Mobile app feature (“Summarize this ticket”) | Product backend | Backend → MCP: service credential (client cred). User context propagated as JWT or user ID header. |

| Pure unattended (nightly batch, scheduled agents) | Job runner / microservice | Service-to-service token only. User context often absent or deferred via signed job token. |

The security envelope expands as soon as humans other than the owner of the target resources are involved.

When it comes to local and remote MCP servers in an enterprise setting, the reality is you will wind up forking or wrapping off-the-shelf MCP servers to accommodate your authentication/authorization needs.

But when it comes to building SaaS products, it gets a little bit more involved, and warrants some more ideation and discussion.

Not much of what is described in this blog post is unique to MCP—you could easily replace “MCP Server” with “Rest API” and most of these considerations still apply—it’s simply that we are re-learning these lessons in the realm of MCP as the spec and implementations and thought leadership evolves around it.

5. Propagating Identity – Dual Tokens & OBO

It is worth digging into a hypothetical example of a real world SaaS product to illustrate the inherent unavoidable complexity involved in properly propagating user context through a call chain from a frontend through a backend and through a set of collaborating services, which in this case includes an MCP server.

Imagine your MCP server receives a call from your SaaS product backend. In an ideal world (which we are so often very far away from), that backend authorizes itself in with its own token issued through client credentials grant flow, and forwards the end-user’s JWT access_token, so the MCP server can do user-level validation and security trimming.

Key points:

- Two tokens travel together (

Authorization: Bearer <serviceJWT>andx-user-token: Bearer <userJWT>). - MCP validates both.

- If CalendarAPI trusts your IdP, MCP can perform an On-Behalf-Of exchange to get a new access token valid for CalendarAPI.

As always, treat user tokens as PII; never log them.

6. Long-Running & Async Tasks

Finally we arrive at the very complex scenario of long-running (perhaps hours or days long) tasks that may be initiated by humans. I am going out on a limb when describing the approaches that can be taken here, because they are not very standardized, but I believe I have some ideas that can assist in making call chains like this more cryptographically secure.

Example: A user kicks off, or configures, an AI-driven workflow that runs for multiple hours and needs to utilize the user’s identity to access various services. This workflow may even run in some type of scheduled way unattended from there on out. The original JWT access_token representing the user expires after an hour, as is typical and proper with most IdP’s. (Note: this is not unlike scenarios you can find in low-code tools like Power Platform.) We have some options:

6.1. Refresh Tokens

- The agent process (acting as an MCP client in this case) stores an (ideally encrypted at rest) refresh_token representing the user.

- The agent process swaps the refresh_token for fresh JWT access_tokens with the IdP, scoped to desired target resources, as needed.

This is likely the most “proper” approach to this today, and has precedence in various services out there. But there is a trade-off: storing a person’s refresh_token is essentially storing a session for them, and is inherently high-privilege; thus these refresh_tokens should (and I would say, must) be protected at rest. They can also be revoked on user off-boarding, which is usually the responsibility of the IdP, but your implementation should gracefully handle if/when a refresh_token is revoked.

6.2. Signed Job Token

-

At task creation, the agent itself issues a JWT, perhaps by using the original user’s JWT or its signature to sign the new JWT with a timestamp claim inside of it, with storage mechanisms for both user + newly issued JWT for later verification (think along the lines of how we use code signing certs to sign source code—the code signing cert may be long expired, but as long as it was valid at signing time, it provides those integrity assurances):

{"sub":"alice", "scope":"export:1234", "exp":now+3h, ...} -

Agent presents the original user’s now-expired JWT access_token plus the newly minted JWT signed by the original JWT access_token in HTTP headers to MCP endpoints dedicated to the job, and MCP knows to validate the original JWT signature,

aud,sub, but not to pay attention to itsexp(expiration), but rather utilize theiat(issued at) claim to understand if the child JWT with the timestamp was signed during a period when the original JWT was valid.

In this approach, there is no long-lived refresh_token required, and the scope is tightly bounded—however, it also requires any endpoints that might receive such a JWT to implement very sophisticated logic of validating a child JWT token based on its signature from another JWT, which many off-the-shelf JWT validation libraries will struggle to do (which means you may be rolling up your sleeves to implement some of this).

6.3. Service account with embedded user claims

- Worker runs with service auth only.

- It stores userID + allowed resources in job metadata.

- Every downstream query constrains rows by that userID.

The tolerance level for using basic strings to represent user context throughout short-lived and long-lived call chains depends on many factors. Your ecosystem may or may not be tolerant to simple user id strings that could potentially be spoofed if someone had an anchor point to call a backend service in your ecosystem. Further, there may be third party API’s you wish to hit as the user which you do not control, in which case you would inherently need some type of super principal that has access to everything in that third party and extra logic to filter based on the user.

Some type of cryptographic material representing the user (a refresh_token potentially that could be exchanged for

fresh JWT access_tokens for a given user when needed) will always be stronger than just representing the user in an

HTTP header like x-user-id: <userId>.

Pick the approach that aligns with your org’s security model and compliance burdens.

7. State of Today’s MCP Servers – A Gentle Rant

Most open-source MCP implementations assume a trusted localhost and a single user. Spin one up for a hackathon and

it’s magic; deploy it in prod and you’ll suddenly need:

- Plug-and-play OAuth/OIDC support (ideally configurable with an IdP).

- Multi-tenant storage abstractions out of the box for product scenarios.

- Hooks for per-request security trimming.

- Token exchange helpers (OBO, OAuth 2 Token Exchange draft).

- Auditing and rate limits.

Today you’ll find yourself bolting these on—or writing a custom gateway—because upstream doesn’t ship them. That’s not a knock on the maintainers; it’s a sign the ecosystem grew up in a local-first culture. But the demand for hosted MCP is exploding, so the tooling, and more importantly the patterns and practices, need to catch up.

8. Conclusion

Context in MCP isn’t just the corpus you feed the model—it’s the environment your server inhabits. Keeping everything on your laptop? Enjoy the blissful simplicity. The second you move to a team, a customer, or the public cloud, bring your security A-game:

- Authenticate every request.

- Authorize every slice of data.

- Propagate identity with care.

- Design for token lifecycles, not solely one-shot calls.

If you’re building an MCP server, plan a two-mode strategy:

- Dev mode: Runs wide open on

localhostfor fast iteration. - Prod mode: Pluggable OAuth, per-tenant isolation, audit logs, and the rest.

Your future self—and your security team—will thank you.

Ultimately, context is everything—not just in prompts, but in the infrastructure that serves them. Let’s make our MCP tools as context-aware as the models they power.

Bonus: A2A and ACP Protocols

Hot on the heels of MCP are the new A2A and ACP protocols which can be used to complement MCP, and while I won’t delve into the details of those in this blog post, I’ll just note that both require similar authentication and authorization considerations to be enterprise-grade and production-worthy, and I may delve more into specifics around those in a future blog post.

I wrote this post mostly to address a lot of FUD (Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt) around how MCP servers operate today and their AuthN/AuthZ strategies (or lack thereof), and should the need arise I can take a similar stab at addressing A2A and ACP.

The world of AI is moving fast, and on the one hand it is great that we are getting open standards and specs so quickly, but on the other hand it will take a little time for them to become fully “fleshed out” with enterprise-grade patterns and practices.